I just wrapped up a sermon series on the seven deadly sins, and I have to admit, I learned to appreciate that little list more than I expected. I hadn’t seen it used all that much outside of tv shows (don’t tell me you’ve never seen a hero fight their way through a band of seven deadly sins themed goons), but it brings more to the table than schlocky action fodder. It’s actually a really great reflective tool that can help draw our attention to the parts of our life that may not be as Christ-centric as we want them to be.

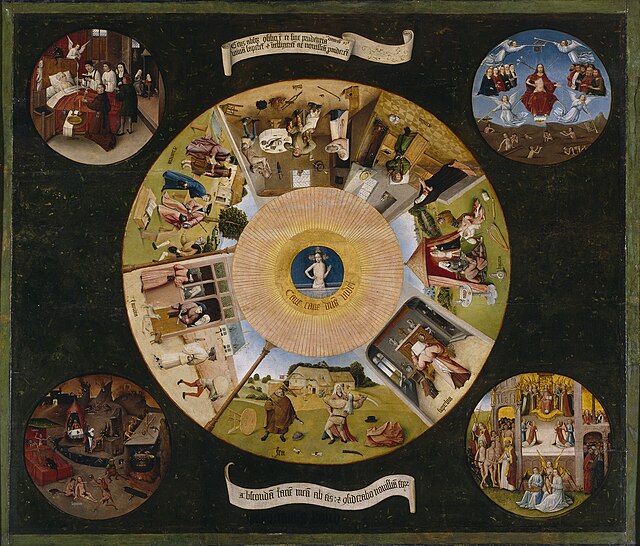

If your seven-deadlies knowledge falls somewhere near where mine was a few months back (zero), let me give you a brief overview. The list of seven deadly sins is a tool that Christians have been using for well over a thousand years with its origin going all the way back into the fourth century. The seven sins are pride, greed, lust, gluttony, envy, sloth, and wrath. The theory here is that most of the sins that you’re engaged with on a daily basis have their roots in one of these seven big sins. If you can focus on those seven things, your life will be much, much holier. In short, it’s a contemplative tool for rooting out sin in your life. You look at the list, you look at your life, and then you see where you have to make adjustments. It’s been significantly more popular in Catholic circles than Protestant ones (we’ll get to why), but you can see why people use it. It’s easy to apply. It’s not hard to understand or wildly theoretical. It’s pretty straightforward for devotional use or sermons or whatever else.

Not only was this a useful tool to add to my tool belt, but it was a delight learning about where it came from and how it was taught. The people that developed this tool were big names in the ancient Christian world that all had a reputation for living holy lives. Reading some of their works was a great opportunity to soak in some timeless wisdom. But before I get to them, I want to talk about someone who comes up in a lot of articles about the seven deadly sins that wrongly gets credit for creating them: Tertullian.

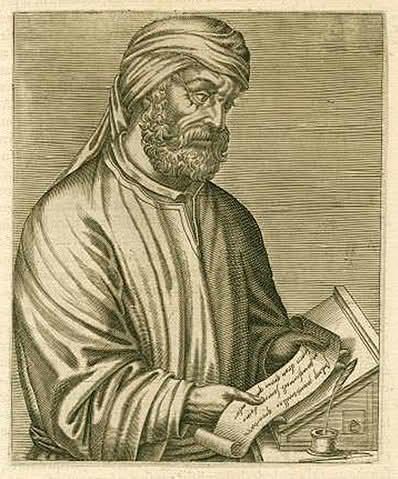

The Red Herring: Tertullian’s List of Unforgivable Sins

Tertullian was a massive theological name in second century Christianity. It’s not surprising that a lot of content can be traced to him. That said, the list of the seven deadly sins isn’t from him. He does have a list of seven sins, but relating them to the “seven deadly sins” as we know them today is such a wild stretch that I can’t imagine anyone who has actually read Tertullian’s work making that connection. His list of sins may happen to contain seven items, but the goal is wildly different. He isn’t trying to tell you about some major sins so you can keep an eye open. No, Tertullian is trying to tell you about sins that are literally unforgivable.

[T]here are some sins of daily committal, to which we all are liable… if there were no pardon for such sins as these, salvation would be unattainable to any. Of these, then, there will be pardon, through the successful Suppliant of the Father, Christ. But there are, too, the contraries of these; as the graver and destructive ones, such as are incapable of pardon — murder, idolatry, fraud, apostasy, blasphemy; (and), of course, too, adultery and fornication; and if there be any other violation of the temple of God. For these Christ will no more be the successful Pleader: these will not at all be incurred by one who has been born of God, who will cease to be the son of God if he do incur them. (On Modesty, Ch.19)

To consider this the origin of the seven deadly sins, we would have to ignore the fact that there’s not a single sin on the list that’s also on the list we know today AND ignore the fact that the function of the list is so wildly different from lists today AND we’d even have to ignore the fact that Tertullian’s list isn’t limited to seven items. Notice that he ends his list with a catch-all for anything he missed: “and if there be any other violation of the temple of God.” It’s not even really a list that’s intended to be limited to any given number of items. It would be absurd to consider this a serious forerunner to the seven deadly sins, especially when you take a look at the next theologian with a claim to the title of originator:

Monkish Wisdom: Evagrius Ponticus and the Eight Evil Thoughts

Evagrius was a monk in fourth-century Egypt, which was the hotbed of Christian monasticism in its day. He wrote a book called The Praktikos (The Practices) to help other monks live holy lives. Sure enough, that book had a list of eight evil thoughts that was intended to be a list of big sins to root out in your life. And when you think about it, doesn’t it make sense that a list like this began with monks? The contemplative evaluation of your life combined with a fervent hope that hard work and effort can bring about virtue and holiness are exceedingly monkish. It also helps explain why the list gets more traction in Catholic circles than in Protestant ones! If you think that you need works and faith for salvation (as Catholics do), a list of major vices is obviously helpful. If you think that faith alone brings about salvation (as Protestants do), the list’s focus on human action and its lack of references to Christ might be considered a little concerning. Not that it’s unusable for Protestants, of course, but it certainly would be viewed as less helpful and maybe a little strange.

Evagrius’s “eight evil thoughts” (or the Ὀκτώ γενικώτατοι λογισμοὶ in his words, which actually translates to something like “eight general tempting thoughts,” but that’s much less catchy) is the first list that shows an obvious attempt to create something like what we know today, and it’s undeniable when you look at his writings:

There are eight principal kinds of tempting thoughts, that contain within themselves every tempting thought: first, that of gluttony; and with it, that of sexual immorality; third, that of love of money; fourth, that of sadness; fifth, that of anger; sixth that of acedia; seventh, that of vainglory; eighth, that of pride. We cannot control whether these tempting thoughts can agitate the soul or not; but whether they remain in us or not, and whether they move the passions or not – that we can control. (The Praktikos, 6)

You’ll notice that there’s still significant work to be done before we reach our final form. At this point, we’re missing envy and sloth. Instead, we have sadness, vainglory, and acedia (a Greek word that’s hard to translate that means something like “spiritual boredom” or “apathy”). On the whole though, the list is really close.

Evagrius’s proceeding advice is pretty hit or miss. Even in the selection above, you can see that he makes some connections that most of us today would just kind of scratch our heads at. For example, why does he connect gluttony and sexual immorality? To us, they’re totally different things. To Evagrius and his immediate audience, it’s obvious that if you’re feeling lustful, you ate too much. The weird parts are definitely there, but there’s some really relatable stuff too. For example, his warnings about the challenges of acedia (boredom):

It makes the sun appear to slow down or stop , so the day seems to be fifty hours long. Then it forces the monk to keep looking out the window and rush from his cell to observe the sun in order to see how much longer it is to the ninth [hour, i.e. 3 pm], and to look about in every direction in case any of the brothers are there. (Ibid. 12)

That is painfully relatable, and definitely helps me think about how much time I fritter away on the days that I’m not particularly diligent about my work. Evagrius has created a great tool for monks, but it needs a pastoral touch to get it to a place where it’s applicable to the average person. And luckily, it would make its way to the perfect person. One of Evagrius’s students, John Cassian, compiled a lot of Egyptian monk wisdom into a wildly successful book called The Institutes and it helped lay the foundation for Western monasticism. One of the monks that was formed by it’s wisdom happened to become pope, and that monk was named Gregory the Great.

A Pastoral Touch: Gregory the Great and the Seven Principal Sins

Yes, the guy who helped get the seven deadly sins to their (mostly) final form was a pope. If you’re Protestant, don’t freak out. John Calvin, one of the biggest Protestant names in history, insisted that Gregory the Great was the last good pope, and if a prominent reformer who was persecuted for Protestantism was cool with him, maybe we should be too.

Gregory’s work on the seven deadly sins appears in a wildly different context. He wasn’t trying to make a list of sins for monks to think though. Actually, Gregory ended up crafting his list while in a commentary on the book of Job. Weirdly, he was exegeting Job 39:25, “At the blast of the trumpet it snorts, ‘Aha!’ It catches the scent of battle from afar, the shout of commanders and the battle cry,” which is actually God talking about how Job could never make an animal as amazing as a horse, which is a pretty far cry from something you’d expect to lead to a discussion on the seven deadly sins. Medieval Christians thought that every Bible passage had several different layers of meaning, some of which could be pretty abstract. In his section about the moral interpretation of the horse passage, Gregory argues that it’s actually about the life of a Christian and how they’re supposed to behave. The line “The shout of commanders and the battle cry,” leads to discussion about spiritual warfare, and thus follows the seven deadly sins that we need to watch out for:

For when pride, the queen of sins, has fully possessed a conquered heart, she surrenders it immediately to seven principal sins, as if to some of her generals, to lay it waste. And an army in truth follows these generals, because, doubtless, there spring up from them importunate hosts of sins. Which we set forth the better, if we specially bring forward in enumeration, as we are able, the leaders themselves and their army. For pride is the root of all evil, of which it is said, as Scripture bears witness; Pride is the beginning of all sin. [Ecclus. 10, 1] But seven principal vices, as its first progeny, spring doubtless from this poisonous root, namely, vainglory, envy, anger, melancholy, avarice, gluttony, lust. For, because He grieved that we were held captive by these seven sins of pride, therefore our Redeemer came to the spiritual battle of our liberation, full of the spirit of sevenfold grace. (Morals on the Book of Job, Vol 3, Pt. 6, Book XXXI, 87)

At this point, I think we have what I’m comfortable calling the modern list of seven deadly sins. Even here, there are a few noteworthy things that are a little different. The name, obviously. Just like the “eight evil thoughts” name got made up to describe what Evagrius was talking about because it was way cooler than the title that came up with, “seven deadly sins” got made up because the actual name that Gregory came up with, “the seven principal sins,” isn’t all that catchy. That said, it’s actually a more accurate title. These are the seven main sins you’re involved in, not the seven sins that will kill you. When did “capital” become “deadly?” Honestly, I can’t tell you. It wasn’t Gregory’s doing, and most formal theological treatises call them the seven capital sins well through the middle ages and even into early modernity. It looks like something that just kind of bubbled up in popular imagination over time.

A second difference that’s worth noting is that vainglory is still here! A weird amount of sources say that Gregory removed vainglory and added pride, but I can’t find a shred of evidence that they’re right. This list very much proves the opposite. Pride is listed as “the queen” of the seven deadly sins, but not actually one of them itself. Instead, pride is defined more closely as the willingness to step away from God, whereas the immoral act of exhibiting what we would call pridefulness in other circumstances is referred to as vainglory. It’s actually a pretty clever solution. Most modern explorations of the seven deadlies that I see simultaneously list pride as the root of all sins AND one of the seven, which is a little clunky. It may as well be six deadly sins and their ringleader at that point. Kudos to Gregory for solving the problem before it happened. Pride is defying God; vainglory is glorifying yourself.

As weird as Gregory’s exegesis of Job may be, his section on the seven deadly sins is actually really applicable. I used Gregory’s wisdom liberally in sermon preparation. Sure, not everything he wrote is applicable today, but he clearly understands the trials of the human heart and that’s universal. He’s also very clear about how each of these sins may be separate,but really, they all intertwined. Lust leads to pride. Pride leads to envy. Envy leads to anger. They’re all connected, and they’re all in our lives. A mature Christian isn’t free of these problems; they should actively be involved in fighting them. If we’re not fighting them, it’s not because they’re not there; it’s because we’re not paying attention.

It reminds me a little of a question I used to ask in confirmation classes. These classes always have a mix of actually religious kids and kids that are just going through the motions. After a lesson about sin, I would ask the kids to rate how close to perfect holiness they thought their daily lives really were. From my perspective, it was an obvious opportunity for a little moment of repentance. Of course you rank yourself low! You’re a sinner! You just saw what God’s standards are! You’re not living up to them, right? Surely, all the kids would admit that they weren’t really doing as well as they wanted to, and then we could pivot to talking about Jesus. It didn’t really work out that way. The less religious a kid was, the higher they would rank themselves on the holiness index. Some kids unironically gave themselves a nine out of ten and said they were doing a pretty good job at keeping God’s law. Try pivoting to Jesus’s sacrifice on the cross after a kid said they’re really actually pretty holy on their own. It doesn’t work. A person can be so blind that they can’t even see their situation clearly. You have to be aware of sin if you want to fight it. That’s one of the best things that this list brings us. In Gregory’s strangely horse-themed words:

But the soldier of God, since he endeavors skillfully to pursue the contests with vices, smells the battle afar off; because while he considers, with anxious thought, what power the leading evils possess to persuade the mind, he detects, by the sagacity of his scent, the exhortation of the leaders. And because he beholds the confusion of subsequent iniquities by foreseeing them afar off, he finds out, as it were, by his scent the howling of the army. (Morals on the Book of Job, Vol 3, Pt. 6, Book XXXI, 91)

Ultimately, that awareness is what the list of seven deadly sins is intended to develop in us. I know it felt convicting preaching my way through them. It’s easy to see the sins of others, but it’s a little trickier to be aware of the sins in ourselves. I hope that some of that conviction stays with me.