Why did Jesus heal the man in John 9 by making mud out of spit?!? I preached on John 9 recently and to make sure I had a good take, I looked up explanations from as many wise Christians as I could. People are all over the map on this one! There are so many explanations! I’ve sorted the theories into six major camps and added a quote from someone that I think is a great source for that explanation. Are there more theories out there? Absolutely, Feel free to do even more searching. I do, however, hope that this captures most of the breadth of the conversation. These ideas definitely aren’t mutually exclusive, so there are a lot of people that pick out several different reasons and agree with all of them.

(A lot of these quotes come from Christians throughout history, which means the primary sources can be tough to read. These are my paraphrases for ease of reading. Feel free to look up the original if something particularly. interests you.)

A Series of Symbols

The Lord came and what did He do? He unveiled a great mystery. He spat on the ground and He made clay out of His spit. Why? Because the Word was made flesh. Then, He anointed the eyes of the blind man. The man was anointed, but he still couldn’t see! Jesus sent him to the pool of Siloam. But notice that the evangelist pointed out the name of the pool: “sent.” And you know who was sent for us! If he hadn’t been sent, none of us would be free from sin! So he washed his eyes in that pool called sent — he was baptized in Christ!

-Augustine of Hippo, Tractate 44 on the Gospel of John

A Test of Faith

“The intention of Christ was, to restore sight to the blind man, but the way he went about it seemed absurd at first. By covering his eyes with mud, Jesus doubled his blindness! Who wouldn’t have thought that he was mocking that poor man or just doing some pointless nonsense? But Jesus intended to test the faith and obedience of the blind man so that he could be an example to everyone else. It wasn’t any ordinary test of faith! But the blind man relied on Jesus’s words alone. He was fully convinced that his sight would be restored to him. With that conviction, he hurried to follow Christ’s command. It speaks to his wonderful obedience that he simply obeyed Christ, even though there were so many excuses to do otherwise. When a devout mind, satisfied with the simple word of God, believes entirely in what seems incredible, that’s the true test of faith. Faith is followed by a readiness to obey, so that anyone who is convinced that God will be their faithful guide will naturally give their life over to God. Who could doubt that fear and suspicion crept into the man’s mind? He knew he might get mocked for what he was doing! But with hardly any effort, he broke through every barrier to faith and realized that it was safe to follow Christ.”

-John Calvin, Commentary on John

The Evangelistic Theory

“Maybe our Lord intended to draw even more attention to the miracle. A crowd of people would naturally gather to see something so odd, and the guide that helped the man get around the city would end up sharing the story as they went to the pool of Siloam.”

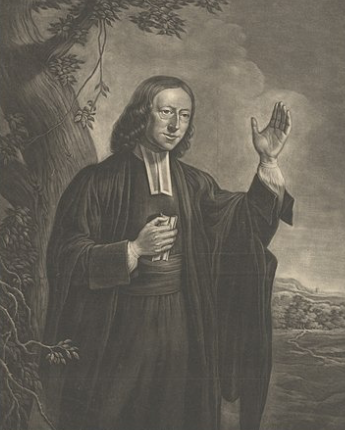

-John Wesley, Explanatory Notes Upon the New Testament

The Gospel Comparison

“The man’s eyes were opened after a little clay was put in them and he washed them out in the pool of Siloam. God really does bless humble things during our process of conversion. It is incredibly humbling for a preacher who thinks, ‘I preached an amazing sermon on Sunday,’ to find God didn’t use that sermon to convert anyone! It was the random remark he made in town the other day that God worked with. He didn’t think it was worth anything! He didn’t plan it out or perfect it! But God did. What he thought was his best didn’t mean all that much to God, but when he wasn’t even trying, God blessed him. A lot of people had their eyes opened by little moments that had an incredible impact. The whole process of salvation is accomplished in simple, humble, everyday things. It’s so easy to compare it to the clay and spit that Jesus used. I don’t know many people that had their souls saved by formal, lofty processes. A lot of people join the church, but I haven’t met any that were converted because of a profound theological debate. It’s not common to hear that someone was saved because the pastor was so eloquent. Don’t get me wrong! We all appreciate eloquence. There’s nothing wrong with it! But eloquence has no spiritual power. It can’t transform our minds, and God prefers to use humbler things in His conversion. When Paul set aside human wisdom and decided not to use eloquent speech, he let go of things that weren’t going to be useful for him anyway. When David took of Saul’s elaborate armor and took up a sling and stone, he killed a giant! And the giants of today aren’t going to be conquered any better by people trying to put on the armor of Saul. We need to stick to simple things. We need to stick to the plain gospel and preach it plainly. The clay and the spit weren’t an artistic combination. It didn’t’ suit anyone’s taste! Nobody felt culturally gratified by that mud! But by that and a wash in Siloam, eyes were opened. It pleases God to use the foolish things to save those who believe in Him.”

-Charles Spurgeon, The Healing of One Born Blind

The Healing Spit Theory

The spittle of a human being is the best antidote for the poison of serpents, though, our daily lives attest to its efficacy and utility, in many other areas. We spit to keep ourselves safe from epilepsy and to avoid bad luck after meeting someone with a bad right leg. We apologize to the gods for having ridiculous expectations by spitting into our laps. In the same way, whenever medicine is employed, it’s good to spit three times on the ground to help it to take hold.

-Pliny the Elder, Natural History Book XXVIII, vii

A Meditation on Means

The Lord revealed his power more effectively by choosing this method of healing than if he had opened the blind man’s eyes with just a word. He used things that seem more likely to blind a man than to let him see! Who would believe that someone was about to heal the ears of a deaf man if they started filling his ears with mud? Clearing his ears might make sense, but putting mud in them? No. If Jesus wanted to use rational means to open this mans’ eyes, a surgical knife would have made more sense than mud. But Jesus chose to use this means for his power… it is supremely easy for him to heal by any means he wants. He can use laying on of hands or touching or a word or even spit and clay. If the word of Christ is added, any means he chooses will be effective, even if it seems more harmful than helpful to us.

-Wolfgang Musculus, Commentarii in Ioannem as found in Reformation Commentary on Scripture.