The split between contemporary and traditional worship is one of the great dividers of Protestant churches in our time. If we’re being honest, a great deal of that split comes down to music. Do you prefer singing soft rock from Christian radio stations? Or do you prefer classical hymns from around the year 1700 until around 1970? For a lot of people, the answer to that question determines what kind of service they’re going to be looking for. But what is there for people that like the oldies? I’m talking about traditional traditional music. No, not that newfangled Gregorian chant. I mean that really old stuff. I’m talking about the psalms.

The English word “psalm” comes from the Greek word psalmos which was a type of sacred song that was sung to a harp. In Hebrew, the book of Psalms is called tehallim. It comes from the same root as the word “Hallelujah” (hll are the three letters both words are built around), and it means “praises.” These aren’t poems. They’re songs. They’re meant to be sung during worship, usually by chant (which was the easiest way to get large groups to sing a song together before sheet music was widely available). Not only were the psalms sung in Jewish worship (including during the time of Jesus), but they were so important to early Christians that a fair few councils in the first thousand years of Christianity went out of their way to encourage people not to sing anything other than the psalms of the Bible. For example, canon 59 of the Council of Laodicea (held in 363 AD) reads, “No psalms composed by private individuals nor any uncanonical books may be read in the church,” (trans. Schaff). That’s not to say you can’t find any hymns from these eras. You certainly can, but mature Christians leaders were constantly calling Christians back to the basics. Sing the psalms. Before you start singing anything else, sing the psalms.

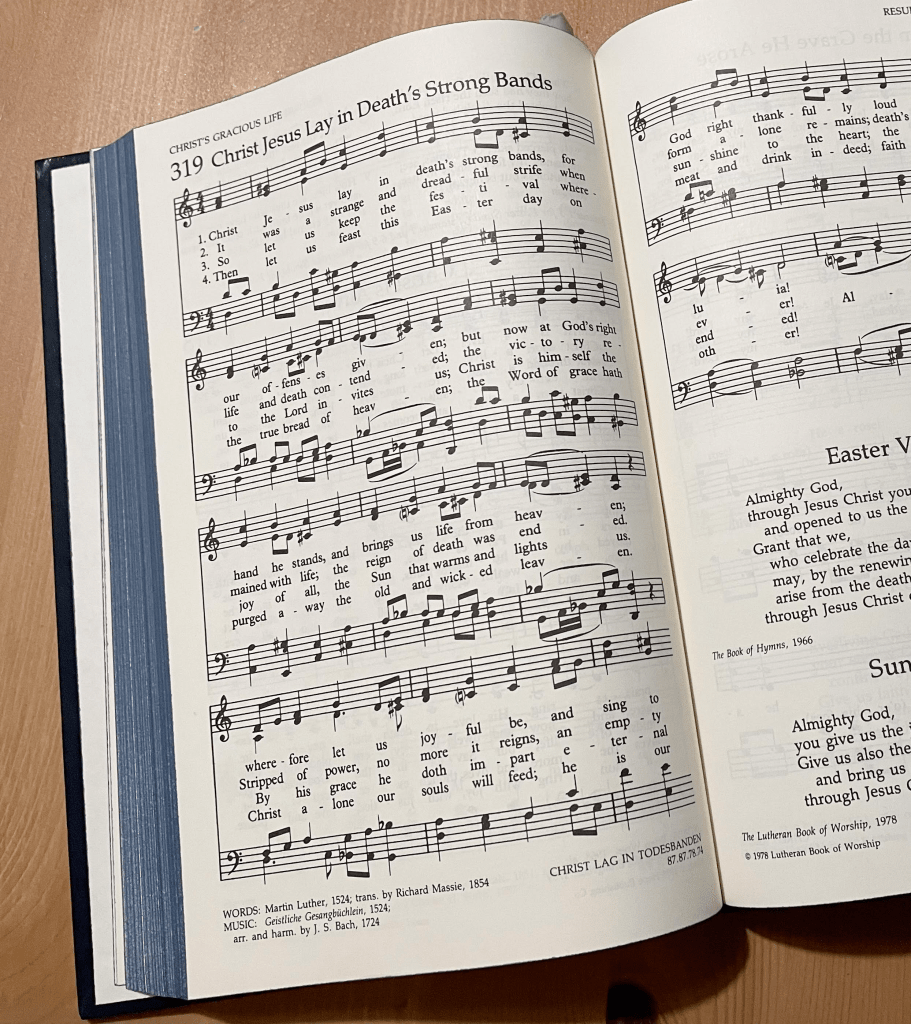

The particulars of congregational worship became less of a concern of the average person in the Middle Ages. Every song (be it psalm or hymn) was sung in Latin, which the average person didn’t speak. They couldn’t join in because they didn’t even know what was being sung. Choir monks handled the singing duties on their behalf. For the early Protestants, the Reformation wasn’t just about taking back the Bible; it was about taking back worship for the average person. While some groups favored the use of hymns (Lutherans), Reformed and Anglican Christians stuck to the Book of Psalms. It wasn’t until the 18th century that writers like Isaac Watts popularized and spread what we think of today as hymns in English-speaking countries.

That sense that we ought to be singing the psalms is pretty rare today. While some of us favor guitars and some favor organs, there aren’t many that are particularly interested in singing psalms. Which is a real shame! For thousands of years, the psalms were the mainstays of Christian worship. And why? Did our ancestors lack the lyrical creativity that we have? Were they too dull to come up with any real hit songs? No! They sang the Psalms because they didn’t think you could do any better than Scripture. As great as hymns like A Mighty Fortress is My God (that one happens to be my favorite) might be , they’re not Scripture. If there’s one little piece of worship music that sticks in a person’s head in a given week, why not have it be one of the songs that Jesus sang? Why not have it be a psalm?

But what about our hymns?!? What about trendy, newfangled pieces like “Rock of Ages” and even trendier pieces like “In Christ Alone”? Is it time to get rid of them? Of course not. And if we’re being honest, I don’t think that’s a realistic fear at this point. These are the songs we know. We love them, and they’re quite good. We don’t have to abandon them. We could, however, afford to add the older oldies to our mix. Take a minute today and find an arrangement of a psalm that you like. Youtube is full of them. There are orchestral arrangements, contemporary pieces, and even chants. You’ll find something that you can enjoy. Not that you’ll enjoy it all, of course, but you probably don’t like everything on the radio or in the hymnal either. Even if it takes a few minutes, take the time to do it. The psalms are your spiritual heritage, and they were made to be sung. Give them a try!