This entry is part of a series called “The Gospel in a Postmodern World.” Learn more about the series here.

Preached on November 13, 2022

Scriptures: Psalm 119:161-168, Judges 17:1-13

Comedy of Errors at an Elegant Downtown Restaurant

The chair is really a table making fun of itself.

The coat tree has just learned to tip waiters.

A shoe is served a plate of black caviar.

“My dear and most esteemed sir,” says a potted palm to a mirror, “it is absolutely useless to excite yourself.”

I remember my English teacher reading this poem by Charles Simic to the class back when I was a junior in highschool. When he was done, he asked us what it meant. One student said that maybe Simic was trying to talk about how objects take on their own personalities over time. Not a bad guess, but the teacher just nodded his head and kept waiting for more answers, so we kept going. Another raised their hand and suggested that the author was talking about how we treat objects better than we treat people. Again, solid guess. But still, the teacher just kept waiting with that stoic look on his face. A few other people took a stab, but nothing seemed to satisfy him. Finally, an uncomfortable silence settled over the room. He said, “I noticed all of you were trying to tell me what the author meant. What if he didn’t have anything in mind when he wrote this? What if this is just a random thing he wrote down? What if YOU’RE the one who has to decide for yourself what it means?”

He was introducing us to that classic dilemma within literature: where does the authority to declare the meaning of a piece lie? Is it with the author, is it in the work, or is it with the audience? If the author is the person who has the right to tell us what their piece really means, the best way to learn more about it is to read a biography about them. The more we can learn about them, the more we can figure out what it was they were trying to get at. But if you think the work itself has authority, you may not want to waste your time with a biography. The author might have created something that they didn’t even fully understand! Spending more time with the work itself will reveal things that they might not have dreamed of. Pablo Picasso was famously in favor of this way of looking at things. He would paint something and then critics would say, “Ah were you trying to get at this?” and he’d respond, “You know, when I painted it I didn’t think I was, but now that you pointed out it’s very clearly there. You’re right.” And then, of course, the meaning might rest with the audience. Who cares what the creator wanted to say? What do you experience when you’re engaging with the work? How does it make you feel? How does it help you to see things in a new way? That’s what it’s all about.

Where does meaning lie? Where is the authority: the author, the work, or the audience? This question broadly correlates to three different eras that we’ve been talking about (premodern, modern, and post-modern). In real life, we have those same three possible sources of authority available to us today. We’ve got an author (God), we’ve got a work (creation), and we’ve got an audience (ourselves). Where does authority lie? Each era answered the question differently.

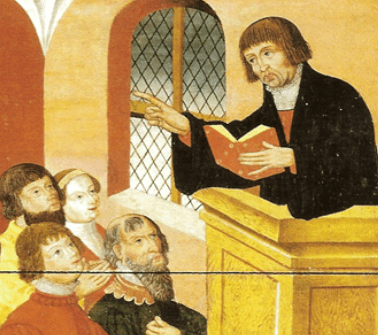

In the pre-modern world, especially from the Middle Ages until around 1700, it was broadly assumed not only that there was definitely an author of all of creation, but that author had the authority over everything. If you look at the way their society was structured, it was deeply, deeply religious. Political theory was steeped in faith. The economy was highly religious. Even their everyday language was constantly pointing to God. Something as tiny as a basic greeting had a religious dimension to it. Instead of “hello,” you might get something like, “God be with ye,” or “God save you.” And why? Because they assumed if you really want to understand things, you look to God. God knows the meaning of everything. Look to Him and you’ll know what’s going on. You can see that attitude reflected so clearly in their writings. I’m going to stick with poetry to explore the thought processes in each era because, you know, pick a motif and go with it. John Dunn’s poem, Death, Be Not Proud, is a great example of thought in the Middle Ages:

Death, be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadful, for thou art not so;

For those whom thou think’st thou dost overthrow

Die not, poor Death, nor yet canst thou kill me…

It goes on from there in that same general spirit. What’s he drawing trying to draw attention to? God. We see this thing called death, and it might look scary, but it isn’t as bad as we think. If you have faith in the author of creation, in God, you have to recognize that death isn’t anything to fear. Look up to God and you’ll know how everything works out in the end. God makes sense of the world, even in the face of death.

Now let’s move forward to the Modern Era. In the 17th through the 20th centuries, people started to think differently. They said, if there is an author out there (and who can say whether there is or not), he doesn’t seem to do much. Let’s not worry about authors. Let’s worry about the work: creation. Clearly creation has certain laws, regardless of where they come from. If we understand those laws, we will understand existence. So people set about uncovering those natural processes that governed creation.

Some people think of this as a great scientific revolution. A time of light, as opposed to the darkness that came before it. I mean, the movement was called, “the Enlightenment,” so that’s certainly what they were trying to invoke, but I would push back on that. Yes, there were some great advances in technology during this timeframe, that much is undeniable, but was it really as totally unprecedented as some make it out to be? I don’t think so. Science was advanced in startling ways in a lot of timeframes. If it weren’t for the accomplishments of Medieval scientists that came before them, people like Alcuin of York, Roger Bacon, William of Ockham, Thomas Aquinas, Duns Scotus, and others, much less the thinkers of antiquity and before them. No, the heart of the movement wasn’t nearly as scientific as it sometimes presented itself to be. No, the biggest difference was that philosophical change in perspective: the world is its own authority. We just have to understand it’s laws if we want to live well. To see that in action in a very unscientific way, let’s take a look at Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease observing a spear of summer grass.

My tongue, every atom of my blood, form’d from this soil, this air,

Born here of parents born here from parents the same, and their parents the same,

I, now thirty-seven years old in perfect health begin,

Hoping to cease not till death.

What’s Whitman excited about? Nature! This air! This soil! This blood! Natural things are good. There’s an earthiness that makes all of creation worth paying attention to. It has value in and of itself. Don’t look up! Look out. Look to creation. It will tell you all of the meaning that needs to be known.

And then, of course, we have the Postmodern Era which we have discussed at length throughout this series. That’s where you end up with poetry about shoes getting fed caviar. What’s the point? It’s up to you. What does the work bring up in you? What journey do you undertake internally when you encounter creation? That’s what matters.

As you go through each era, you can see how people think about meaning and order. The pre-modern mind saw a sacred order. God at the top, everything goes around him. The modern mind saw a natural order. Keep the order in mind and you’ll figure things out as you go. In the postmodern world, you make your own order, because there’s no natural logic to the things out here. The world is what you make of it.

I know some of you may not be big fans of poetry, so thank you for suffering through those examples with me. You can see these philosophical elements in any artistic medium, though. I just chose poetry because I liked it and it’s short enough to get to quickly, but you can choose anything you like. Think about literature. Dante’s Divine Comedy is a perfect example of a pre-modern story. A man goes through Hell, Purgatory, and then Heaven, detailing things along the way. We’re literally observing the divine order at work. You move into the Modern Era and you have Walden. It’s just a guy living in the natural world. The whole point is showing the beauty of living well within that natural order. And then take something from today, for example, A Song of Ice and Fire a.k.a. Game of Thrones. It may not be exactly a literary classic but it’s a story that got a lot of people’s attention. Who’s the good guy in Game of Thrones? No one. There’s no divine order. There’s barely any order at all. Everyone is trying to seize power for themselves because where does power lie here? You. You decide what the world is and you try to make what you can of it.

You start in the medieval section and you will see art everywhere depicting divine beauty: Jesus, saints, and angels. Then you move forward a little and what do you see? Landscapes. People want to capture the beauty of the natural world. And the further on you move, the more you see the landscapes start to vary. Artists like Monet and Van Gogh start to paint landscapes from perspectives that earlier artists would never have imagined. And then, of course, you get to contemporary art and things just fall apart. I saw one exhibit that was just a fence leaning against the wall. If they didn’t have a plaque with the artist’s name next to it, I’d have assumed they were just doing construction! I even googled it and found that exact fence on sale at Home Depot for $219. You too can have an art installation in your home for the low, low cost of $219.

As we move through these different philosophies in each era, from seeing the authority in an author, to seeing authority in the work, to seeing it in ourselves, you would think it would be like a process of taking off shackles. Theoretically, we should be the freest people of all time. We should feel lighter than air! We should be freer than ever since we’re only answerable to ourselves! But if that’s the case, why is our Postmodern Era so typified by existential dread? Why do so many people wake up in the morning and ask themselves, “What’s the point? What am I even doing here? What’s the point of any of this?” It turns out, when we’re the only ones with authority and we invent our own meaning, it’s really easy to remember that it’s all nonsense. We made it all up! It’s pointless. If we get frustrated or bored by what’s going on, the sheer arbitrariness of it all is right there, staring us in the face. Is it any wonder that people can’t be bothered to enjoy a meaning that they know they’ve made up? Why bother reading a book or a speech or short story when all of it is nothing more than an opportunity for me to expound upon myself. Things feel pointless because in many ways, they are. When the world is bound by the smallness of our own horizon, it seems so tiny. We have nothing to live for! We have nothing to die for! It’s all tremendously shallow.

This is not the first time that these sorts of ideas have taken hold. There’s this temptation to assume that whenever something happens, it’s happening for the first time ever. That’s rarely the case. Here, we can see in the Scriptures a period not so very different from the one we inhabit; a period where people see no legitimate authority outside of themselves. Let’s read through Judges chapter 17 carefully.

Now a man named Micah from the hill country of Ephraim said to his mother, “The eleven hundred shekels of silver that were taken from you and about which I heard you utter a curse—I have that silver with me; I took it.”

Then his mother said, “The Lord bless you, my son!”

Right from the beginning, this story should strike you as odd. What a strange opening! A man steals his mother’s fortune. It’s 1,100 shekels of silver. We don’t need to do any kind of ancient conversion rate to figure out that this is a lot. Near the end of this story, someone is promised ten silver shekels of silver annually for a job and he takes it without complaint. If ten shekels a year is a decent wage for one year, this is massive! He’s set for life! But he stole it from his mother, who curses whoever took the silver, so he brings it back. And what’s her reaction? To bless him.

Why? Returning the money you stole because you’re worried about a curse is better than keeping it, of course, but it’s not exactly an example of sterling behavior. Maybe it’s worth lifting the theoretical curse over, sure, but giving a blessing? Why? He hasn’t done anything good! He barely managed to avoid the obvious evil that he was headed towards! He hasn’t earned anything! Even though he’s a sketchy guy, he gets a blessing. I’m sure only good will come of this.

When he returned the eleven hundred shekels of silver to his mother, she said, “I solemnly consecrate my silver to the Lord for my son to make an image overlaid with silver. I will give it back to you.”

So after he returned the silver to his mother, she took two hundred shekels of silver and gave them to a silversmith, who used them to make the idol. And it was put in Micah’s house.

There has been some debate among commentators about what exactly was intended by the word “idol” in this particular story. Is this idol intended to represent a being other than God, or is this idol a visual representation of the god of Israel? I tend to assume the latter. She essentially says, “Thank the Lord! I’ll have this idol made,” so to me that tips the scales towards an idol designed in service of God, rather than Baal or someone like that. But here’s the thing, it doesn’t actually matter in the end. Either you’re making an idol for some other God, in which case you are guilty of breaking God’s law because you made you’re worshiping some other God, which is wrong, or you’re breaking the law by making an idol, which is against God’s law regardless of the intent you had when you made it.

God explicitly forbids idols multiple times throughout the Scriptures. It’s in the Ten Commandments! Don’t make idols! Why? Because even if the idol is intended to serve God, idolatry fundamentally reverses the divine order. God created us. We are in his image. When we turn around and create idols, in some sense we’re turning around and creating God. We’re designing him in our image. God is not subject to the smallness of our understanding.

The pattern of disordered behavior continues. At first, a blessing went to a thief. Now an idol goes to God because someone wants to thank him.

Now this man Micah had a shrine, and he made an ephod and some household gods and installed one of his sons as his priest.

Even if I was right earlier and that first idol was intended to serve God, Micah has decided that one god wasn’t enough. He’s filling out a little pantheon for himself, giving his main god some little friends. Then he designs his own priestly garb and finds a priest to hire. He’s got his own little religion going on! And then we see the through line for the whole book of Judges:

In those days Israel had no king; everyone did as they saw fit.

This line appears throughout Judges, and it’s one of the last lines of the entire book: in those days, Israel had no king; everyone did as they saw fit. It’s not necessarily a reference to a physical King. Not long after Judges ends, Israel does get someone to be king and God warns them that they don’t need a king over Israel. He warns them that he should be their king and that any king other than him is going to make all kinds of mistakes. But they tell God, “That’s a little abstract for us. We’re not really into the whole ‘king we can’t see’ thing. We’d rather just get a physical king just like every other nation. Thanks!” So they get a king, and he’s pretty rotten. The point here is not just that there’s no physical king; it’s that there’s no authority. There’s no god that anyone really acknowledges. They are their own authority. They do what they want.

A young Levite from Bethlehem in Judah, who had been living within the clan of Judah, left that town in search of some other place to stay. On his way he came to Micah’s house in the hill country of Ephraim.

We’re introduced to this Levite, a priestly figure, out traveling around. He’s looking for somewhere to stay. We don’t know why, but we know he has responsibilities back home. For whatever reason, he’s out and about and he meets Micah…

Micah asked him, “Where are you from?”

“I’m a Levite from Bethlehem in Judah,” he said, “and I’m looking for a place to stay.”

Then Micah said to him, “Live with me and be my father and priest, and I’ll give you ten shekels of silver a year, your clothes and your food.” So the Levite agreed to live with him, and the young man became like one of his sons to him.

Micah hires this Levite away from his responsibilities in Bethlehem. And notice that at the end, it says that this Levite became like a son to him. In Roman Catholic churches today, people refer to priests as “Father,” partially to show reverence to a religious authority, but here this Levite is just the opposite! He’s “like a son.” This priest isn’t someone he’s going to submit to. He’s hired a false authority for show, but he retains authority over this Levite.

Then Micah installed the Levite, and the young man became his priest and lived in his house. And Micah said, “Now I know that the Lord will be good to me, since this Levite has become my priest.”

What an absurd statement we get to end this story. This man has done nothing but break the God’s law since the story began. He stole money from his own mother, he made an idol, he invented new gods, he started his own religion, and then he hired a corrupt priest to serve as the head of this new religion. And he sits back and thinks, “Yeah, God must be pretty happy right now.” Why? He’s never done anything that God wanted. He’s only done what he wanted. He imagined what he thought a good divine order might look like, he usurped traditional elements and ritual to make it look like it had some dignity to it, and now he’s bought in to what he himself invented. He’s not interested in worshiping God! He’s only interested in legitimizing his own self-worship.

All too often, that is the way Christians approach church today. Is there an interest in God? In church? In his divine order? No. But there is an interest in legitimizing self-worship with traditional elements and ritual. We come to church with our lives just the way we like them and tell God, “I’m happy with the way I’ve arranged things. I just need you to sign off on it. Please tell me it’s ok to break your law. You want me to be happy, right? So approve of what I’ve done! Tell me you’re happy. Tell me you’re happy! Tell me you’re happy!”

The whole thing reminds me of a theory by the famous mystic Evelyn Underhill. She once explained the goal of life by telling people to map their lives out on paper. Write the central element of your life in the middle, and then everything that serves that center all around the page. For most people, their name goes in the middle of the page, and most events in their lives are intended to serve them. God ends up in a corner of the page, propping up their ego. In this model, the assumption people carry is that God exists to serve them. People assume that if everything serves them, they will be happy. Ironically, it makes them miserable. We long for something greater than ourselves to serve. As long as we’re using all of the elements in our lives to serve ourselves, we’re eternally frustrated by just how shallow everything seems. If we want to make a better map, we start with God in the center and design everything in our lives around him. How are we serving him? How is our life a part of something greater than ourselves? Serving God brings joy!

I think she’s right. I think she’s absolutely right. In a world where there’s a sense that we ourselves are the ultimate authority and there’s no meaning outside of ourselves, we Christians have the meaning of life at our fingertips! But there’s a temptation to slink back and say, “Maybe they’re right. Maybe I am the authority. Maybe all of these religious trappings are intended to serve me. God is here to endorse my order. He’ll like what I do. He’ll sign off on it.”

But if we do that, we are denying the world something it desperately needs. People are waking up every morning asking, “What’s the point?” People desperately crave to know that there’s a point to all of existence. For crying out loud, they’re reading poetry about feeding caviar to shoes and they’re staring at gates! We can do better than that! People are seeking legitimate beauty! Legitimate truth! Legitimate authority!

We have to accept God’s authority to understand any of that. We have to seek to serve Him, rather than ourselves. There is an authority outside ourselves. There is an author, and he carries incredible authority over creation, revealed to us most completely in his word. The great missionary, Leslie Newbiggin once said, “If we cannot speak with confidence about biblical authority, what ground have we for challenging the reigning plausibility structure.” In other words, we can’t present a genuine Gospel to the world if we can’t trust that God’s authority, as put forth in his word, is actually legitimate. No, we need to look to Scripture and see how the God that we claim to serve is communicating with us! Talking to us! Telling us what the point is!

Of course, sometimes, it’s hard. Sometimes, the things God asks of us in Scripture are incredibly difficult. Some of his ways don’t seem to serve our wants at all. The world might look on and say, “What are you doing? Why don’t you just live an easy life?” Nobody remembers people who live easy lives. Nobody writes stories about people that did nice, easy, normal things. Nobody writes a book about someone who went and got coffee one day. People read stories about heroes that slay dragons and save kingdoms. People crave stories about people who overcome the odds for something greater than themselves. That’s something we have the opportunity to do: to serve something greater than ourselves.

For the past three sessions (not counting our Reformation Day detour), we’ve talked about Postmodernism. We’ve talked about the ways that the church is, in many aspects, on the back foot. We’ve talked about truth; in the postmodern world claiming to know objective truth is seen as arrogant. How do we communicate in a way that seems humble without giving up on truth? We’ve talked about sin; in a world where the assumption is society is the sole corrupting force, how do we acknowledge the sin that rests in the human heart? Both truth and sin are complicated to discuss honestly with people outside the Church. It violates popular thought in ways that are often seen as offensive. But when it comes to authority, I think we may have something intriguing on our hands. It’s something that doesn’t violate the orthodoxy of secularism in a way that’s obviously offensive, but is still outside of the norm enough to make people hesitate and ask, “What?”

If we started to live into God’s authority, REALLY started to live into it, we would probably be perceived as pretty weird people. We’d be those Christians; the ones who take it a little too seriously. Too often, we try to distance themselves from those Christians. We try to seem religious, but not too religious. We try to be approachable and cool. That’s proven pretty ineffective. Looking at attendance rates in larger denominations, the more a church ignores the uncomfortable bits in Scripture to seem cool, the more their attendance rates plummet. The more a church presents a Biblical counterculture to the world, the more likely they are to grow. I don’t mean to oversimplify things by suggesting that attendance proves that something is right. Obviously popularity is a poor substitute for truth. But I do mean to suggest that people outside the church are seeking more than just an institution willing to rubber stamp the dominant cultural order. They’re actually more interested in a weird place that they don’t fully understand than they are a safe place where that affirms their own authority. Weird isn’t all bad.

When you’re weird, you show that you’re willing to break from a status quo that’s proving itself ineffective. You also become the kind of group that earns a second glance from people. Have you ever stopped to look twice at something normal? No! Of course not! You see a million normal things every day. Why on Earth would you stop to look at one more normal thing any longer than you have to? But something weird? You may well stop and look for a minute! This thing, foreign though it may seem, is different. It’s got something to say. That’s a huge advantage to the Church, if we’re willing to take it.

Some churches do, and it proves surprisingly effective. I remember one Pentecostal girl in seminary that spoke very well on this. When I met her, I asked her about tongues because that’s what you do when you’re talking to someone who’s Pentecostal! You talk about tongues! It’s a rule somewhere I think. We chatted about it a bit before I said, “You know, it must be really hard to evangelize because that’s really out of the norm. I mean I think it’s weird and I’m a Christian! I already agree with you on like a huge chunk of things that non-Christian people don’t, and I think your understanding is, forgive my saying it, strange. It must be infinitely more challenging to talk to non-Christians about your faith, since this is a significant part of it.”

She responded, “Are you kidding me? It’s so much easier for me to evangelize. People want to talk to me. They come up and say, ‘You’re Pentecostal, right?’ and I say, ‘Yeah.’ And they say, ‘But you obviously don’t believe in that tongues stuff, right?’ and I say, ‘I don’t just believe in it; I’ve seen it. Come and see!’”

I may not agree with the way Pentecostals understand tongues, but wow, that’s a good sell. I almost went to church with her there and then. “Come and see!”

In a world that isn’t used to accepting authority outside of themselves, there’s a shallowness that many feel. Increasingly, people crave something bigger than their own thoughts and whims, and we have something they’re looking for. Something weird. Something that should be forcing us to live in a way that’s totally different from the people around us. If we’re honestly accepting the authority of God as presented in the Scriptures, people should have to look twice! If we’re living the way that we’re supposed to, there should be conversations a lot like the ones she experienced.

“You’re a Christian, right?”

“Yeah.”

“But you don’t believe in any of that weird stuff do you?”

“Yeah.”

“Wait, so you actually think there’s a God that you can talk to and outdated laws he wants you to keep and an objective point to all of this?”

“I don’t just believe it; I know it. Come and see.”