This entry is part of a series called “The Gospel in a Postmodern World.” Learn more about the series here.

Preached at The Plains United Methodist Church on October 30, 2022

Scriptures: 2 Peter 1:10-21, Romans 1:8-17

Happy Reformation Day, everyone!

I’ve noticed a lot of Methodist churches don’t regularly celebrate Reformation Day, which is a shame. It’s a great opportunity to look back at our own history; to see where we’re from and what some of our core DNA is. We need to give it the attention it deserves. At one of my past appointments, I spoke about Martin Luther during the sermon, and afterwards a woman came up to me and said, “Wow, Martin sounds great! I haven’t met him yet. Does he go to the other service?” Who can’t blame her for what she doesn’t know? It’s on us pastors for not teaching it enough.

For those curious, Martin Luther did not go to the other service. Martin Luther lived in the 16th century. He was the founder of Protestantism. Without him there would be no Methodists! There would be no Anglicans from which Methodists could come! Not only would there be no Protestants, but what we know today as the Roman Catholic Church would look different as well. Martin Luther is a big deal so I think it’s worth a little time to tell his story and remember about one of the great Protestant heroes.

I want you to imagine that the year is 1521. You are in an imperial court in the city of Worms, a city that’s in what we know today as Germany, but was known back then as a part of the Holy Roman Empire. This room is full of some of the most powerful people in the world. Among them is Charles V, the singular man who is the archduke of Austria, the Prince of Spain, the lord of the Netherlands, the duke of Burgundy, and the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. He is a big deal. There’s also a papal envoy dressed in some of the finest clothes imaginable. In front of that envoy, a monk stands next to a pile of books.

The envoy speaks: “Martin Luther, this court has reconvened. Yesterday we asked you two questions. The first: ‘Are you the author of these books in front of you?’ You answered yes. Our second question: “Do you renounce the ideas contained therein and recant your heresy?’ You asked to be granted a 24-hour recess. This was granted, but we are back today, Mr Luther, and we need an answer. Do you renounce the ideas contained within these books and recant your heresy?”

You wouldn’t have expected things to turn out like this given where this story starts. It starts in a little kingdom called Saxony. Saxony was not the kind of place where life-altering things tended to happen. It was in Northern Germany. Northern Germany wasn’t well developed. It was really rural. Southern Germany had a lot of stuff. Northern Italy had a lot of stuff. Northern Germany? Not so much. There were no ruins of an old Empire to build on. There were no great trade routes. Most of their top items to sell were natural resources; grain, fish and minerals. Saxony wasn’t the kind of place where big things happened.

None of that was helped by the politics of Saxony only a few generations back. When King William II of Saxony died, his two sons split the kingdom and each inherited half of it. The elder brother got to choose how the lands were split, and the younger brother got to choose which area he wanted to inherit. And so the elder split the lands: one of the two parcels was a long, twisty portion of land that was mostly rural, and the other was a little clump of land that had all of the major cities in it. The choice fell to the younger brother: did he want to rule the urban center of the lands, or the larger rural area? He took the urban area, leaving the elder brother, a man by the name of Ernest, the jaggedy rural strip.

Since Ernest was the elder and got second pick of the lands, he got something extra: the title “Elector of the Holy Roman Empire.” I don’t want to get too far into the weeds describing the political system of 16th century Germanic kingdoms, but here’s a really basic understanding: imagine if the United States had a weak federal government and strong state governments. In this model, the president would still exist, but he would appear on the global stage to represent the collective interest of the states. Individual states would have a lot of autonomy. The president wouldn’t really have much say over them. That’s basically what the Holy Roman Empire was. There were a bunch of really small kingdoms, some so small that they were just singular cities, all bound together in mutual interest and represented by an emperor that they got to elect. Not everyone got to vote for the emperor though. Only a very small group called “the electors” got to vote. Ernest may have inherited the rural lands, but he was an elector, and that made him, strangely, an important man with a somewhat unimportant kingdom.

That’s the legacy of 16th century Saxony. Not exactly the center of the world. But when Ernest passed away, his son, Frederick the Wise, was looking to change all that. Frederick was bound and determined to make little Saxony the kind of place where things happened. The capital of Saxony, Wittenberg, only had 2,000 people in it and 400 buildings, but it was the biggest city there was in Saxony, so that’s where he started. He created two plans to make Wittenberg a destination for people all over the world.

The first was to create the biggest collection of relics the world had ever seen. Relics were basically Christian artifacts. The presiding theory of the day was if you looked at a relic God would bless you. It was a very mechanistic process. Look at the thing? Get the blessing. Frederick started collecting relics and managed to get his hands on over eighteen thousand of them. He even managed to collect a vial of milk from the Virgin Mary and a twig from the burning bush. Now, you can decide if you think those relics were legitimate or not, but people at the time thought they were VERY legitimate. Pilgrims started flocking to Saxony to see all of his relics laid out in Wittenberg’s chapel. They wanted to soak up all of God’s grace that they could!

Frederick’s other plan was to build a university in Wittenberg. He’d build a massive, top-notch university and people would come from all over the place to attend! Maybe, some of them would even stick around and become citizens of Saxony. So he started hiring professors. He even bought one of those newfangled printing presses! Printing presses were a bit of a curiosity at this point. Books weren’t all that common. They weren’t even written in language that the average person understood. They were only in Latin, the language of scholars. Frederick wasn’t sure how exactly this printing press was going to help him, but new things were exciting and his university would have nothing less but the very latest in technology.

Even with Frederick’s ambitious plans in full swing, the average person would not have expected much from little Saxony. Nor would people have looked at the hero of the Reformation, Martin Luther, and expected great things from him. Martin was from a middle-class family. His dad owned a mining business and managed the business side of things, which was both expensive and risky. He had to take out loans to buy the mining rights to a piece of land and he never knew when there might be a cave-in or flooded tunnel that would impact his ability to pay off the loan properly. He spent most of his life in debt as he took out and paid off different loans, but all things considered, he was pretty good at what he did. The mining business did well enough, so he sent his son, Martin, off to college in a place called Erfurt, a big city in the area, in the hopes that he would become a lawyer. If he was a lawyer, Martin would be able to help the family business a lot.

That was not to be. Martin went to college, and one day, while he was coming back to campus from a little trip, there was a storm. We’re not just talking about a little rain. We’re talking about howling winds crashing thunder! Lightning struck right next to him! He was sure he was going to die. He prayed to God, “Let me live through this and I will do whatever you want. I will give my whole life to you,” and the storm subsided. So, true to his word, he gave his life to God and became a monk. His father was not particularly enthusiastic at first, but he warmed up to it over time. He saw his son’s sincerity and wanted what was best for him. So, Martin started living in his local Augustinian monastery there in Erfurt. He found a mentor that he really admired. Things were going well! Unfortunately, his mentor moved away. There was this little university that was just getting started up in Saxony’s capital, Wittenberg, and it was hiring up all of the professors that it could. Since Martin’s mentor was both a monk and a professor, he took a job and transferred over to a monastery in Wittenberg. Unfortunately, Martin didn’t have a lot of friends around the Erfurt monastery after his mentor left. The other monks weren’t on the same page as him. They decided to transfer him to their branch in Wittenberg so that he would be near his old friend and out of their way. When you’re a monk, you don’t really get a say in the matter. They’re not asking if you’d like to be transferred; they’re telling you that you’re getting transferred.

You might think that Martin would be overjoyed to be back with his friend. He was not. He was really frustrated. Wittenberg was full of nothing! All of Saxony was full of nothing! That was the kind of place where barbarians settled! Nonetheless, as he settled in, things turned out pretty well for him. He became a pastor and worked at the local church. His mentor helped him get on-staff at the university where he taught as the professor of biblical theology. Everything was slowly turning out ok.

Now we have the right person (Martin) in the right place (Wittenberg) for the Reformation to kick off, but there’s one critical element we haven’t discussed: the powder keg. The event that blew up and kicked everything off. At the time, the Catholic Church was selling something called indulgences. An indulgence was basically a little certificate from the pope that said all of your sins were forgiven. They were also transferable. You could buy one and apply the forgiveness to someone else. A lot of people would buy them for their dead relatives. The popular assumption of the day was that your dead relatives were probably in purgatory. Heaven was only for the super holy Christians, Hell was for non-Christians, and purgatory was for Christians that were too sinful to make it into Heaven. God would purify them over the course of a few thousand years until they had been fully cleansed of their sins. That process of purification was said to be pretty unpleasant, so you wanted to help your dear sweet relatives get out of there in any way you could. Buying the pope’s indulgences was the best way to get grandma to Heaven.

I’m sure many of you find that thought process unthinkable, but there’s a long series of ideas that were accepted over time before selling indulgences started to make sense. I won’t go through all of it, but it starts with ideas like, “Well, if you go to a holy site, isn’t it reasonable to think that God would bless you?” Sure, ok, that makes sense. God probably blesses pilgrims that go to holy sites. “Well, what if Christians do something to help others? Like defending them from persecutors by going on crusade? Will God bless them for doing that?” Ok, sure, intellectual baggage of the crusades aside, maybe it’s reasonable that God would bless people that set out to help others in unfortunate circumstances. “Well now, what if you donate a large amount of money so that someone else can do those things? Wouldn’t that also deserve a blessing? Because you’re the reason someone else can do it.” Right there, you’ve already got the fundamental framework for indulgences. You’re just a hop, skip, and a jump away from writing certificates.

Martin hated the church’s sale of indulgences. They were getting ready to sell them in Saxony for the third time in five years. Saxony wasn’t wealthy! Why did they keep selling them there? And all the money from the indulgences was going to fund repairs of Saint Peter’s Basilica, a really fancy church in Italy. Why did the pope need the money of peasants to fund a church for the wealthy? And Martin saw the negative effects that indulgence sals had on people, both rich and poor. Poor people that had to scrimp and save so they could buy a certificate for grandma to go to Heaven. The rich, on the other hand, didn’t worry as much about living a Christian life when indulgences were around. They could do whatever they wanted as long as they made sure to grab a certificate for themselves when they were done. The whole thing had gotten completely out of hand.

As this was happening, Martin had a rapid spurt of spiritual growth. He was someone who seemed to have it all: he was a professor, he was a monk, and he knew his Bible forward and back! But he had a dark secret: he hated God. Martin hated God because he thought that he would never be good enough for him. The popular theory to explain how law and grace functioned in the Christian’s life was via something called “imbued grace.” They thought that God gave you enough of his grace to go out and keep the law pretty well. If you made mistakes, well, then God would be angry. If you asked for forgiveness, he might punish you a little less severely, but you would still be punished to some degree. And after it was done, you were expected to go and live a perfect life again. Martin believed it, just like everyone else, and so he tried very hard to live a life without sin. He realized that when he really thought about what he had done on a given day, there was always sin to be uncovered. There was always a moment when he was jealous or when he was short with someone, and so God was always angry and waiting for him to do better. His best wasn’t good enough.

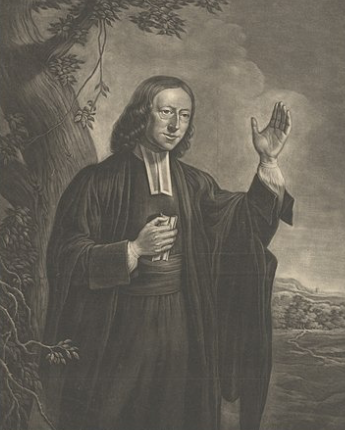

But everything changed when he was teaching a class on Romans. Romans is like that. Some of the most famous Christians of all time converted while reading Romans. Saint Augustine, one of the most famous Christians of the 4th Century, converted while reading Romans. Martin Luther converted while reading Romans. John Wesley converted while reading Romans. The book of Romans is powerful. Let’s look at one of the passages that was on the top of his mind. This is Romans 1:8-17:

First, I thank my God through Jesus Christ for all of you,because your faith is being reported all over the world.

This is a letter from Paul to Roman Christians and you can see that he’s impressed with them. He’s impressed that they have such incredible faith in a place like Rome. Christians in Rome endured a lot of persecution. Torture and even death, depending on who was in charge at the time. It would have been incredibly dangerous. You would need an impenetrable faith! But this is the kind of church where people had impenetrable faith. They didn’t stumble; they endured.

God, whom I serve in my spirit in preaching the gospel of his Son, is my witness how constantly I remember you in my prayers at all times; and I pray that now at last by God’s will the way may be opened for me to come to you.

In other words, he wants to visit them.

I long to see you so that I may impart to you some spiritual gift to make you strong— that is, that you and I may be mutually encouraged by each other’s faith.

I love the humility here. One of the great apostles says, “I want to give you a gift and the gift… is that you and I get to sit down and build each other up.” Faith is not just a one-way street! It’s something that takes people coming together. People that are mature and very wise and people that are brand new! We all stand to learn and be built up by one another.

I do not want you to be unaware, brothers and sisters, that I planned many times to come to you (but have been prevented from doing so until now) in order that I might have a harvest among you, just as I have had among the other Gentiles. I am obligated both to Greeks and non-Greeks, both to the wise and the foolish. That is why I am so eager to preach the gospel also to you who are in Rome. For I am not ashamed of the gospel,

The gospel would have seemed pretty ridiculous by a lot of the popular philosophies of the day. The average Roman would think that the gospel was nonsense! “Your God’s so great? Well, why’d he get crucified then? A powerful god doesn’t end up dying on a cross. I can find a god more worthy of my worship than that.” The average Jewish person would have been equally disinterested: “Your god is supposedly great, but he hasn’t delivered us from the Romans. I don’t see any grand miracles that he’s done. He rose from the dead and apparently did nothing worthy of note for me.”

But Paul is not ashamed of the gospel, regardless of what others think! He goes on to say why:

because it is the power of God

How often do you think about the gospel in that way? How often do you understand it not just as a collection of words, but as something powerful? As words that crackle with energy? The gospel is the power of God! It’s not just something for us to mull over in our spare time. It’s the kind of force that changes hearts and minds.

For in the gospel the righteousness of God is revealed—a righteousness that is by faith from first to last, just as it is written: “The righteous will live by faith.”

This whole time, Martin had been trying to be good enough. And here we see one of the major themes that comes up again and again throughout Romans: you’ll never be good enough to earn salvation. On our own, we are not capable of perfectly keeping God’s law. God grants us salvation not because of our works, but through faith in Christ. When we reach out and trust in him, that makes all the difference. Our salvation isn’t through legalism. It’s through love! God looks down and sees not a guilty person, but someone who has been cleansed! Who is innocent! Who is pure! Someone covered by the perfection of Christ.

We are saved by faith, not works. Does that mean we should go on sinning? By no means! Paul specifically says that later in this same letter to the Romans. But if our salvation isn’t based on legalism, we should be able to act however we want, right? No! Paul says that a true Christian should be transformed through their encounter with God. We shouldn’t want to sin anymore. We should be totally different creatures, empowered by God to seek what is right instead of what is wrong. And besides that, our motivations for doing what’s right should change. We don’t keep the law out of fear of God’s punishment. We do it out of fear of hurting our relationship with him. We want to make him happy. We should naturally want to honor and cherish the one we love. Our relationship with God may not be based on maintaining a code of conduct, but we should still want to honor the God who saved us with everything we do.

And here, inspired by the words of Scripture, we see Martin articulate one of his big ideas: sola fide. We are saved by faith in Christ alone, not by our works. Not our abilities. Not because we’re good enough, but because we have faith in Jesus. We reach out to him and accept the sacrifice he made on our behalf. Martin’s big idea didn’t come from the intellectual trends of the day, but through scripture alone. There’s another one of his big ideas: sola Scriptura. That’s Latin for “by Scripture alone.” Scripture is the only authority that we can rely on to ensure that we’re practicing real Christianity and not just something that we made up.

Now we’ve got the who, the where, and the what. Everything is in place. Martin Luther started preaching what he had learned in Romans. And the indulgence sellers came into Saxony and started preaching their doctrines. This is a selection from the sermon of a man named Johann Tetzel. He was selling indulgences in Wittenberg, and this is what he preached:

You should know that all who confess and in penance put alms into the coffer according to the council of the confessor, will obtain complete remission of all of their sins… Why are you standing there? Run for the salvation of your souls!… Don’t you hear the voices of your wailing dead parents and others who say, “Have mercy on me, have mercy on me, because we are in severe punishment and pain. From this you could redeem us with small alms and yet you do not want to do so.” Open your ears as the father says to the Son and the mother to the daughter, “We created you, fed you, cared for you, and left you our temporal goods. Why then are you so cruel and harsh that you do not want to save us, though it only takes a little?” (20-21, A Sermon, Johann Tetzel, as found in The Protestant Reformation, Hillerbrand)

THAT was the last straw. THAT was what made Martin Luther write his ninety-five theses. Ninety-five reasons why indulgences were bad! Ninety-five reasons that the pope was wrong! Ninety-five ways the church was failing! And he didn’t just keep this debate in academic halls. He started writing books. These were books written in a language that regular people could actually read. He wrote for the average person because he thought they deserved to know what was going on. He also made sure that people had access to the Bible in their own language so they didn’t have to take his word for it. They could go to the Word of God and look for themselves! He looked to Scripture alone (sola Scriptura) to find the truth, and now everyone else could do the same. Because even if he was eloquent, his words weren’t worth anything. God’s word was worth something. It was and still is the final authority on all things.

Some people get a little confused about Luther’s relationship with tradition They think he brought this new, unheard of understanding to the Scriptures and represented a radical break in Christianity from its past. That is not the case. Yes, he trusted Scripture alone as the ultimate authority, but that doesn’t mean he was ignorant of tradition or uninterested in the Christians that went before him. Read some of his writings sometime! You won’t make it far without finding a citation from one of the great thinkers from the first 1500 years of the faith. The man was a professor that sold books. His goal wasn’t to prevent people from reading and learning from those who went before him! His goal was to reconnect with early Christianity and recover the faith from people who had slowly twisted it over the years. Sola Scriptura doesn’t mean separating yourself from the collected body of Scriptural knowledge and just believing whatever you want to believe about the Bible. It means learning as much about it as you can about God’s word, educating yourself on what it’s saying to you, and taking it as the authority above any earthly thinker, regardless of how popular they might be.

Well, after he posted his ninety-five theses, things got difficult. It turns out posting ninety-five reasons why the pope is wrong doesn’t exactly put you in his good graces, and in those days, the pope was shockingly powerful. Pope Leo X wrote a papal decree called Exsurge Domine, which is Latin for “Arise, O Lord.” It basically said: “Martin Luther, turn from your heresy or burn for your heresy. The choice is yours.” And that brings us back to where we started: an imperial court where a monk is being questioned. He was asked, “Do you recant your heresy?” Here is how he responded:

“Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the holy Scriptures or someone can reasonably prove to me that I have erred (for I neither believe in the pope nor the councils alone since it has been established that they often erred and contradicted themselves) I am bound by the Scriptures which I have cited at length and my conscience has been taken captive by the word of God. I am neither able nor willing to recant. Here I stand. I can do no other.”

From there, things got really crazy. He was whisked back to Saxony, where he went into hiding. Remember how Frederick the Wise was deeply invested in making Saxony a place where things happen? Turns out that no matter how devoutly Catholic he was, he wasn’t willing to give over someone who attracted as much attention and sold as many books as Martin Luther. Martin’s big ideas kept spreading, and more and more people started hearing the things that he was saying. That is how Protestantism started.

Why do I think this story is worth our consideration? It’s not like anybody is going around selling indulgences today, right? After all, why would they? The average person isn’t convinced they’re particularly sinful. They may not perceive themselves to be perfect, but they don’t think they’re a bad person, and that ought to be good enough for God. Works righteousness has made a significant comeback in the modern era; the bar for salvation-worthy works is just a lot lower than it was in Luther’s day.

People simply don’t understand the seriousness of sin anymore! In an environment like this, we need to remember our solas: sola fide and sola Scriptura. From whence comes our salvation? Not from ourselves! Contrary to popular belief, we’re not particularly good. We’re saved because God is particularly good. He’s the only one with the power to save us. The best thing we can do is to trust our lives in his hands. To have complete and total faith in him, rather than ourselves. Sola fide. And how do we know that this is the case? Not because we’ve kept up with the philosophical trends of the day particularly well or because we’ve read the articles that have harvested the most clicks. No. Our authority is not the shifting sands of public opinion. It’s Scripture alone. Sola Scriptura. We look to the word of God and that is our rock and our anchor.

Aside from the solas, Luther’s boldness is so incredible. He stands for what’s true, even knowing that he might be killed for it. That’s the level of boldness that the church desperately needs to reclaim today. Only a few generations ago, it was socially advantageous to participate in a church. It didn’t matter if someone believed any of it; they were happy just to be participating in a normative institution of American culture and reaping the benefits that came along with it. You can find records where businessmen with almost no interest in religion move to a new town and immediately join the local church. Why? So that they can promote their business and be seen talking to the right sort of people. People gave up their Sunday mornings to get something tangible. Churches that participated in that cultural quid pro quo are in a hard place today. Why? Because things don’t work that way anymore. Nobody stands to gain new clients or a good reputation because they go to a local church. At best, the church is neutral on both of those axes, and at worst, it may actually cost them a good reputation to be a regular participant in an orthodox church. The next generation of Christians will not be enticed into Christianity because they stand to gain anything in the secular world. To the contrary, they will have to pay something.

Martin Luther was willing to pay any price when it came to keeping the word of God. I pray that each of us would be willing to do the same should it fall to us.

Amen.